What Is the Anglican Angle?

Dr George Byron Koch

Q. There is an Anglican angle with New Jerusalem House of Prayer. What is that about?

A. New Jerusalem House of Prayer is a member of the Anglican Church in North America. The Anglican Church has had a key role in the history of the State of Israel and a long tradition of working with and caring for Jewish people in that land, even before the State of Israel existed. Below we will briefly unpack some of that history and our connection to it. A bibliography at the end provides further reading for those wishing to know more.

The Beginnings of the Anglican Church

The Anglican Church was originally the English national church of the Roman Catholic Church, even after the Protestant Reformation that began in 1517. The king of England at the time, Henry VIII (1491-1547), was called the “Defender of the Faith” by Pope Leo X. But because of ambitions of his own, and a desire to have his marriage annulled for lack of a male heir, as well as other political forces in England, Henry led the Church of England to break with Rome, seized the property owned by Catholic monasteries and churches, and had himself declared head of the church.

It was the beginning of today’s Anglican Church (or Church of England), and it included much treachery, larceny and ambition. Protestants rose in influence in the church under Henry’s successor Edward VI, and battles raged between them and those loyal to the Roman Catholic traditions. It was a time of awful and murderous struggle for ecclesiastical power in England. You can read more about this period in any good history.

Two key events changed the character of this church and struggle: the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603), who ascended the throne in 1558 and reigned 45 years until her death in 1603, and the creation of The Book of Common Prayer by Thomas Cranmer, the first edition of which was published in 1549.

Elizabeth I effected a time of peace, the “Elizabethan Settlement,” in the English church. Those on the Catholic side and those on the Protestant side were allowed to maintain their theological differences, but prayed and worshiped together using prayers that were prayed in common. This was the role of The Book of Common Prayer, or BCP. The two sides could have divided into separate denominations, but ultimately the church stayed together because it prayed together.

Both streams, now called “Anglo-Catholic” and “Protestant” (as well as several others) continue to this day within the Anglican Church, and elements of each can be seen in most Anglican churches, with some individual churches and dioceses leaning strongly one way or the other. Worship practices range from relatively simple and with plain dress, to elaborate vestments, incense, chanting, liturgies and more. Again, these developments can be studied in any good church history.

Especially in relation to the New Jerusalem House of Prayer, Jewish tradition, and the State of Israel, what is most relevant here is:

- Native cultural leadership raised up by Anglican missionaries

- The prayer book tradition

- The London Jews Society and its ongoing influence

We’ll look briefly at each of these.

Native Cultural Leadership

During the 17th and 18th century, Anglican evangelicals (exemplified by John and Charles Wesley, George Whitfield and others) began sending missionaries to the far corners of the globe. But unlike the missionaries that had been sent by Roman Catholic orders (Dominicans, Benedictines, etc.) and other Protestants, who tended to always have European clergy in charge of churches in other countries, the Anglicans chose instead to educate and train native clergy to lead the churches in their own countries. This had a profound effect on the enthusiasm and growth of the churches and, as a result, the Anglican Church today is the third-largest in the world (behind the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox). It is also the largest Protestant denomination, with some 70 million members, the majority of whom are in Africa and Asia.

Worship was adapted to local language and culture (where they didn’t contradict biblical values), and local and national churches developed their own unique common prayer traditions. They were similar to each other, and followed the lead of Cranmer’s BCP, but they were also culturally sensitive and appropriate.

New Jerusalem House of Prayer follows this tradition as it works to refine worship which incorporates both Jewish and Christian elements, Hebrew and English, and is culturally sensitive and appropriate to both, while also conforming to biblical values.

The Prayer Book Tradition

Prayer books are collections of Scripture, actions, prayers, directions and more that serve to focus a congregation on God and a holy life. The tradition of worship extends back to the order of service in the early synagogues long before the time of Jesus (see chart here), but was not really codified into a book until much later. The prayer book tradition includes both the siddur, the prayer book of the synagogue, and the Missal, Breviary and Ritual, which were the prayer books of the Roman Catholic Church. Cranmer based The Book of Common Prayer on these traditions, though he clearly departed from much of the theology of the Mass in the Catholic books. The contents and sequence of the service stem back to the earliest church, which were rooted in the synagogue tradition.

Some modern Protestants are unfamiliar with liturgy and find its structure somewhat surprising, yet it is not only common, and stands in an ancient tradition, but is in fact the form of service still most common in both Christian and Jewish houses of worship worldwide.

Liturgy is from a Greek word meaning “the work of the people,” and the idea is that the congregation has a key role to play in prayer and worship. The congregation is not seen as an audience before whom the leadership performs, but rather as key participants in all of the worship service. Hence, we have “common prayers” that all pray together, either as one, or responsively.

New Jerusalem’s service is based on the siddur and The Book of Common Prayer, with some adjustments appropriate to our context and goals, and as is typical of missions in other cultures.

The London Jews Society

In the early 19th century, a number of Anglicans in London came to believe that the prophecies of Ezekiel 37, along with some others, were intended by God to be taken seriously and would be fulfilled in modern times. The Israelites had been scattered all over the world. There was no “Israel” in that time. The land now known as Israel was simply a territory of the Ottoman Empire (which they called “Palestine,” a name given to it by earlier Roman occupiers), and the Jews who lived there were mostly rural poor, and living in a culture that had little room or respect for them. But the London Anglicans believed what Ezekiel 37 had prophesied:

O my people,

I will open your graves of exile

and cause you to rise again.

Then I will bring you back

to the land of Israel.

When this happens, O my people,

you will know that I am the Lord.

I will put my Spirit in you,

and you will live again

and return home to your own land.

Then you will know that

I, the Lord, have spoken,

and I have done what I said.

These Anglicans founded the London Jews Society and began to work for the restoration of Israel. Several of their initial steps proved prophetic and critical:

- They established factories in “Palestine” specifically to employ Jews and help raise their standard of living. They began (among others) the now popular olive-wood industry, which produces thousands of crosses, manger scenes and chalices, sold in Israel and all over the world.

- They sent doctors and established medical clinics and hospitals to care for Jews in a land that was without such facilities.

- They established schools to raise the literacy level of the Jews they served, where little education was available to them.

- They supported Theodor Herzl and other Zionists in the movement for a Jewish homeland, contributing funds, time and connections to make this possible.

- They worked with the British Parliament, Prime Minister and military leadership to free the land from Ottoman (Turkish) control, and lead it first through British Mandate rule, and ultimately to independence in 1948.

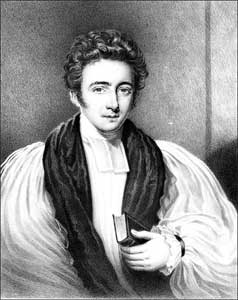

- They ordained a Jewish Christian Bishop, Michael Solomon Alexander, and assigned him to Jerusalem, where he built Christ Church and its associated schools and compound (though he died before its completion):

Bishop Michael Solomon Alexander

None of these steps were without controversy or opposition. Some anti-Semites in Britain opposed the effort altogether. Some prominent Jews in England and Europe supported the effort and welcomed the work of the Anglicans. Some thought the efforts futile and foolishly biblical. Some saw the efforts as an attempt to convert Palestinian Jews to Christianity by helping them with jobs and medical care, and this precipitated a significant effort by some rabbis and Jewish philanthropists to replicate those initiatives, but led by Jews instead of by Christians. If anything, this duplication and acceleration of effort helped precipitate the Zionist movement, and led finally to the creation of the State of Israel. The extraordinary efforts of all of those involved (Christian and Jew alike) are well documented. Some of the major histories describing them are listed at the end.

The London Jews Society is now known as The Church’s Ministry Among the Jewish People, or CMJ. It has branches in many countries and continues to operate Christ Church and its affiliated schools in the Old City of Jerusalem and throughout Israel. Today those schools serve Christians, Jews and Muslims, and work both for a good education, and training in living together in love. Two of the staff members at New Jerusalem serve on the Board of CMJ.

The staff of Christ Church includes Jewish Christians, Gentiles, native Israelis and volunteers from around the world. It conducts services in Hebrew and English, and translates the services via headphones into many other languages. Here’s a picture of the inside of the sanctuary:

Sanctuary of Christ Church, in the Old City of Jerusalem

It looks like a synagogue, and most of the text and decorations are in Hebrew. This is not to “trick” anyone into thinking it is a Jewish house of worship, but rather to acknowledge that the Christian faith is essentially Jewish in its roots, Scriptures, teachings and early leadership. Its founder was a Jewish rabbi named Yeshua (Jesus), who said that “not one jot or tittle” of the Torah would pass away, who celebrated all of the “Jewish” biblical feasts, and who was himself an observant Jew.

This fact makes some Christians and some Jews uncomfortable. But it is a reality that must be faced if either faith is to understand who Jesus was and is. This is one of the issues that New Jerusalem faces head-on, week in and week out, and by the articles that it supplies on its Web site.

There are several issues that continue to separate most Christians and Jews:

- An extreme and persistent anti-Semitism in the Church and society that has caused the persecution, oppression and death of many Jews over the course of 19 centuries. You can read more about this in Persecution of the Jews.

- A disagreement about who and what the Messiah is. Some Jews believe the Messiah is actually Israel itself. Others believe it is a person, but one who has not yet come to redeem Israel and the Jewish people; therefore they believe it cannot be Jesus. Christians believe Jesus is the Messiah of Israel and the world.

- A difference in understanding the nature of God. Most Jews believe that because God is One, there cannot be any “others” in the Godhead. Christians believe that there is One God, but in three persons: Father, Son and Holy Spirit. This is usually referred to as the “Trinity.”

- Some Jews do believe that Jesus was and is the Messiah. These are usually called “Messianic Jews,” or sometimes “Hebrew Christians,” or “Jewish Christians.” Some other Jews don’t believe Messianic Jews are really Jews anymore because they believe in Jesus.

- Some Christians believe Messianic Jews should abandon their Jewishness entirely and adopt the cultural norms of Gentile Christians. This was actually the cause of much of the early division in the church between Jewish and Gentile believers. See The Way of Rabbi Jesus for more detail. It hasn’t improved much since then, sadly.

Summary

As you can see, there is a long and profound history of the Anglican Church and its love for the Jewish people. It believes that as followers of Jesus, we are mandated to love the Chosen People, the Jews. At New Jerusalem House of Prayer, this is something we do not out of obligation, but out of JOY! We have learned and grown SO MUCH as we have studied the Jewish roots of our faith. So much was lost which is being restored. So much was forgotten which is being recalled. So much was despised or rejected which is being honored and recovered.

Our leadership includes both Christians and Jews, as does our membership, and we endeavor to make it a place of prayer where people from both backgrounds are honored and respected, and where ancient Jewish traditions of worship and liturgy are experienced as a part of who and what we are.

We are a member congregation of the Anglican Church in North America, and a part of the worldwide Anglican Communion. We are proud of its history of honoring and respecting the cultures in which it does ministry, and we desire to love and respect the Jewish and Christian members and friends that are drawn to worship with us. You will find this true in our liturgy, order of worship, Bible studies, Hebrew classes, tours to Israel, and our invitation to others to live together with us in a safe and loving family of God.

Bibliography

For the Love of Zion. Kelvin Crombie. Hodder & Stoughton, 2008.

A Jewish Bishop in Jerusalem. Kelvin Crombie. Nicolayson’s Ltd, Christ Church, Jerusalem, 2006. The modern movement of Jewish believers in Jesus and of evangelical Protestants in Israel.

The Jewish State. Theordor Herzl. Dover, 1989.

Our Father Abraham: Jewish Roots of the Christian Faith. Marvin R. Wilson. Eerdmans, 1989.

Exploring Our Hebraic Heritage: A Christian Theology of Roots and Renewal. Marvin R. Wilson. Eerdmans, 2014.

For more resources, see this extensive Bibliography.